Health Belief Model – Its Applications

An earlier blog entry discussed the important role of behavioral science in any employee training effort. This entry discusses the background of one of the most influential behavioral science models – the Health Belief Model.

It hardly seems fair to a beleaguered food service trainer, but students never enter training with their minds completely receptive to the information they are about to hear. That might be true for children but never for adults. The adult mind is not an empty blackboard or open vessel, ready to receive the knowledge and skills trainers have spent many hours preparing to deliver.

Instead, adult students enter the training environment with preconceived notions about what they are about to experience, notions skewed and biased by family, friends, media and a million other influences. The trainer, inspector, auditor, or consultant must anticipate these influences, without knowing them precisely, if their effort is to succeed. If they are fortunate enough to be able to gather data through a short interview or needs assessment prior to the event, then all the better – they can adjust their focus to address those concerns.

The Health Belief Model is a behavioral health model developed to theorize (a) how information might be processed, accepted, or rejected by the student; and, by inference, (b) how the trainer might anticipate and answer those reactions to keep the training program on the right track. It was originally proposed in the 1950s to suggest how tuberculosis patients processed public health information about that illness and subsequently reached decisions about how to act. Decades of public health research provides a solid scientific foundation for this Model.

Note: I’ll stop here a minute to state a condition. While I studied this Model with Dr. Rosenstock at the University of Michigan and feel very confident in this blog entry, my applications to food safety, while logical, are speculative and not based on any research. My attempt to gain my doctorate to study the science behind my conclusions, met with a very cold reception by health educators. It is curious that all sorts of applications are possible. (Source for this section: The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later Nancy K. Janz, RN, MS Marshall H. Becker, PhD, MPH published in Health Education Quarterly Spring 1984)

That said, sanitarians must anticipate how environmental health information will be processed by their clients. It can be done in a short interview or chat prior to any inspection or training effort, or acquired ad hoc, subsequently and revisited at a future date. The failure to acknowledge these processes will result in an unknown ‘black box’ phenomenon where the results are unpredictable. Hence, managers are sincerely mystified that training efforts are unsuccessful; sanitarians are mystified that the restaurants where they spent endless hours working are still called in for enforcement.

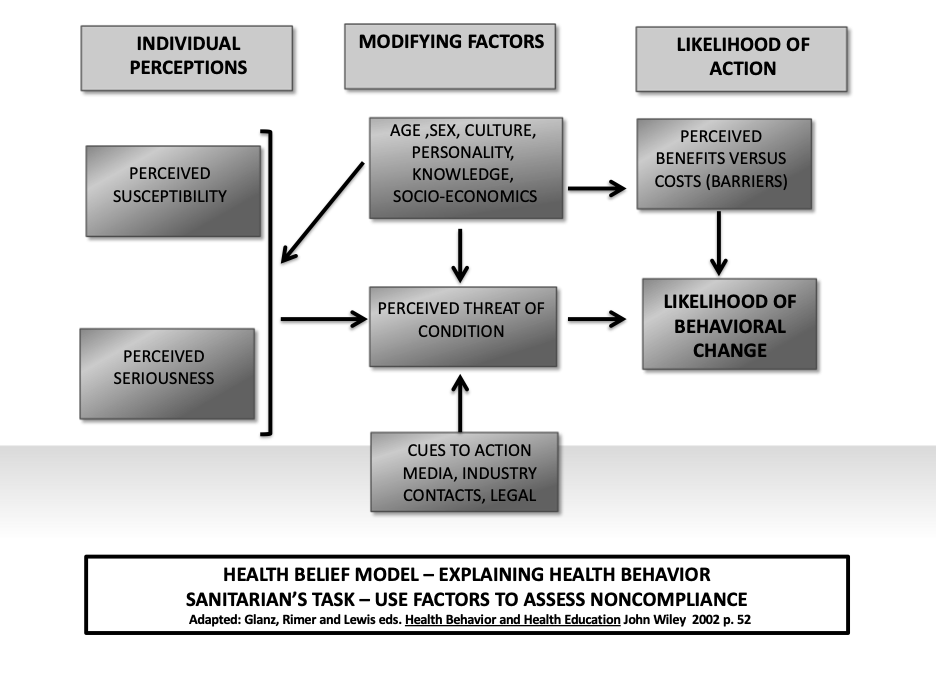

Health Belief Model Structure: The figure above describes the process whereby information is received and processed. The student or client is presented with a recommendation for behavioral change; store foods to avoid cross contamination, cool hot foods rapidly, avoid bare hand contact with RTE foods and so forth.

The client’s reaction is not an impulse though it might seem that way. It is, instead, carefully considered based on two variables: (1) the value placed by an individual on a particular goal (‘will I be affected by this problem, and will the effect be significant?’); and (2) the individual’s estimate of the likelihood that a given action will achieve that goal (‘is the problem really inadequate handwashing or should there be another sink installed closer to the cook line?’). The trainer must be clear that all solutions have been considered and the one presented in the program is the best.)

There are intervening influences on the person’s determination to act. These are described in the center column. While the sanitarian cannot always influence these factors, motivating Cues

to Action can be provided through negative (enforcement) and positive (media campaigns, monetary and media rewards, changes in type and frequency of inspection) factors.

Next, assuming the client agrees action should be taken, they must believe the recommended change is the correct one and that they can make this change, especially after the training is concluded. Put another way, do they believe in their capacity to take the required action, to produce the recommended change? (This is often called perceived self-efficacy). Their belief will be influenced by perceived barriers to change (not enough time to act as required, inadequate equipment).

This process is largely based on the individual’s perception and not always reality. This is one reason why modeling the proposed change in behavior and reinforcing the client’s practice, are vitally important. It not only shows the sanitarian’s confidence in the behavior’s importance, it allows the client to gain mastery of the skill in front of their future evaluator.

Thus, clients do not act ‘off the cuff’ but consider carefully their responses based on their perception of the information provided and the proposed change in behavior. Sanitarians can influence this perception by anticipating possible objections and working solutions into the training program or inspection.

Here are some examples of ways to influence the client’s perception of the Model’s variables:

1) Model desired behaviors during the inspection. If the wrong behavior is observed, take time to model the correct action and reenforce the employees who practice it properly. (This should emphasize the correct behavior as well as allow employees to improve their self-efficacy).

2) Praise positive behaviors when observed (positive reinforcement).

3) Use the office food safety newsletter to describe food safety problems and how good solutions are being applied in the workplace. Also, use the newsletter to report on foodborne illnesses and the results for the restaurant. (Increases problem awareness as well as presenting realistic solutions practiced by others in the industry.)

4) Hold a yearly banquet or meeting to reinforce a restaurant’s good inspection results.

5) Before a training program or inspection, take time to discuss events or interests not related to food safety or public health. (Clients are often surprised to find that sanitarians have other interests outside of their work.)

6) Continually think about the Model’s factors and ways they can be emphasized

Interested in knowing more about the integration of behavioral science in your restaurant, during inspections, or just a friendly off-the-cuff chat? Please email me with your comments, suggestions and requests for service, especially the last one!

Write me at Dave@foodsafetymentor.com THANKS FOR READING 🙂

Read more about: listeria control plan