Chill Out! How to Cool Those Foods Safely

Unsafe cooling of hot foods has been consistently linked to foodborne illness. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that improper cooling methods contributed to 504 foodborne illness outbreaks between the years 1998-2008. (Note that these are outbreaks not individual cases of illness).

First, what are the requirements? Regulations state that TCS (time/temperature control for safety) foods must be rapidly cooled to avoid the growth of microorganisms which either survived cooking (Clostridum perfringens protect themselves from heat by forming spores) or which contaminated foods after cooking. Specifically the rules (FDA Food Code 2017) state….

Time/temperature control for safety (TCS) foods shall be cooled: within 2 hours from 135F to 70F and within a total of 6 hours from 135F to 41F or less. If TCS foods are prepared at ambient temperature, they shall be cooled within 4 hours to 41F or less.

Further, approved cooling methods are described as follows:

Cooling shall be accomplished …by using one or more of the following methods based on the type of food being cooled: (paraphrase) placing the food in shallow pans; separating the food into smaller or thinner portions (slicing up roasts, using several smaller pots); using rapidly cooling equipment (e.g. larger walk in coolers or blast chillers); stirring the food (soups, stews) in a container placed in an ice water bath; using containers that facilitate heat transfer (prechilled or metal containers); adding ice as an ingredient

Food containers shall be…. Arranged to provide maximum heat transfer through the container (containers separated to allow cold air circulation); loosely covered or uncovered if protected from overhead contamination.

The purpose of these rules is to move hot TCS foods rapidly through the zone of unsafe temperatures (danger zone). Bacteria multiply rapidly in the zone between 135F and 70F, sometimes as fast as every 8 minutes.

So how effective are these rules in preventing further growth? What does the research show? (Journal of Food Protection V. 75 (12), December 2012, Pages 2172-2178 Brown, Ripley, Blade, et. al.)

How well do food service managers follow these rules? In one study of 420 full service restaurants, most managers did not follow the FDA guidelines properly. In this two pronged study, managers were interviewed about cooling procedures and data was collected on how foods are actually being cooled. Since the interviews were voluntary, the data indicates real concerns about safe cooling practices.

The good points first: over 90% of managers trained their employees in proper cooling procedures; over 95% reported the use of thermometers to check temperatures; over 75% employed a certified food safety manager (suggesting more knowledge of food safety rules); and over 80% stated an employee was trained to calibrate the thermometer.

Now, the negative aspects of the study: 20.2% knew the correct FDA cooling procedures; 85.5% did not use all the FDA recommended practices (they did not know them or stated them incorrectly); 60% stated that cooling procedures were monitored but only half of those (42.9%) calibrated thermometers. Of the latter group, half stated they calibrated thermometers once a week while only 16.8% stated they calibrated once a day (the recommended frequency). Of those who said they used thermometers to check food temperatures (95.3%), about 40% said that they calibrated thermometers at least once a week; others said that they calibrated at least once a day, at least once a month, less than once a month, never, or they were unsure how often thermometers were calibrated. Since 74.5% used bi-metallic probe thermometers, calibration is critical: the study reports this was done infrequently.

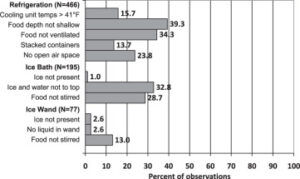

Data collected during site visits showed quite a different story. The FDA procedures were not being followed. 46.6% (466) of cooling steps involved refrigeration. This is good except that about 10% of walk-in coolers, a third of reach-in coolers, and less than 1% of freezers were above the FDA-recommended maximum temperature of 41°F (5°C). This would indicate that heat was not removed, using other methods, prior to refrigeration.

According to the study this is true: only 30.3% used ice bath, ice wand, a blast chiller or added ice as an ingredient. And when other methods were used to remove heat, they were not used properly. Ice baths did not have adequate ice or were not stirred. Foods in refrigeration were not in shallow pans (39.3%), the cooling food was not ventilated or was stacked (48%) or did not have proper air circulation (23.8%). 16.8% used room temperature cooling! Room ambient temperature will rarely drop below 70F suggesting the potential for large growth of bacteria prior to refrigerated storage.

It must be emphasized that there could be many explanations for these concerns, such as training, time and resources. It is also very possible that practices vary depending on language, culture, experience in the industry and the type of operation. The study does indicate however, that restaurants might not be aware of the problems caused by unsafe cooling methods.